Even a generous biographer cannot ignore the utter selfishness at the core of this thinker

KARL MARX died a disappointed man. All his life, he had longed to be a leader. But by impetuously renouncing Prussian citizenship early in his career, he condemned himself to the exigencies of exile. He was obliged to watch while others usurped his role.

Thus he became, less by inclination than necessity, a thinker and a writer, a Rousseau rather than a Robespierre. Although one cannot understand the 20th century without reference to Marxism, Marx himself is – perhaps always was – little and badly read. With the exception of the Communist Manifesto, none of his works has ever had popular resonance. They are difficult. Unless one is familiar with their theoretical and historical background, even his most important writings are at best obscure, at worst unreadable. Any biographer ought to provide that background.

A biographer also needs to engage with Marxís ideas. Do his economic theories hold water, either as a description or a critique of capitalism? Non-Marxist historians of economic thought such as Joseph A. Schumpeter or Eric Roll differ on this. The same applies to his political, sociological and philosophical theories, which have been shot to pieces and reassembled ever since his death. How far were the deeds of communist regimes foreshadowed in Marxís harsh words about those who stood in his way: the peasants, the bourgeoisie, the intellectuals, even the workers?

Most of Marxís biographers have concentrated on his ideas and offered answers to these questions. Francis Wheen does not. He cares little for the political economy or Hegelian philosophy, is no historian and appears to read no German. But he claims to be the first to treat Marx as “a human being”.

Not even the generous Wheen, whose biography of Tom Driberg overlooked his treachery, could be taken in by the humanity of Karl Marx. He emerges as a liar, adulterer, snob, sponger, boor, hypocrite and domestic tyrant. He destroyed everything he touched, from newspapers and clubs to the First International. He ran through several substantial legacies and played the stock exchange while preaching that inheritance and private property should be abolished.

As a young man, he had married Jenny von Westphalen against the wishes of her family. As a father, he forbade his favorite daughter, Eleanor, from marrying the Frenchman she loved, preferring one of his disciples, Edward B. Aveling, who made her his mistress. (Aveling secretly married an actress and persuaded Eleanor to enter a suicide pact. She drank the poison; he did not.) Marx never acknowledged his illegitimate child by his maid and insisted that the boy be fostered to prevent scandal.

Wheen finds it hard to admit that Marx was a man of violent and paranoid racial prejudices, with a severe case of Jewish self-hatred.

The notorious essay “On the Jewish Question” is excused on the grounds that its author was defending the Jews; yet his works and correspondence are peppered with anti-Semitic epithets, usually combined with scatological insults.

But even Wheen is shocked by a repulsive but typical passage about the nose of the then editor of this newspaper, Joseph Moses Levy. Indeed, he believed in the civilizing mission of the Germans, and did not hesitate to appeal to nationalism when it suited his purpose. His Russophobia led him to believe David Urquhartís lunatic conspiracy theory that Palmerston was a Russian agent. Marxism was, in a sense, the ultimate “German ideology”: it conquered half the world.

Where Wheenís biography works well is in its depiction of Marx living the life of a bohemian journalist in Soho. There are delightful anecdotes about Marxís pub crawls and low life, taunting the constabulary or indulging in marathon chess and boozing sessions. Even this more likeable side of Marx, though, only confirms his utter selfishness. His wife, Jenny, a blue-blooded bluestocking, lost four children and lived for years in squalor. She was a loyal wife and secretary, despite the indignity of lifelong financial dependence on Engels (of whom she disapproved). But she was not amused by her husbandís escapades.

Wheen wants us to read Das Kapital as a gothic fantasy, and endorses Edmund Wilsonís claim that Marx was the greatest ironist since Swift.

There may be something in this, but such a defence would have appalled Marx. He loathed the literary pretensions of rival revolutionaries, such as Giuseppe Mazzini and Ferdinand Lassalle. But these men played an honorable part in the unifications of Italy and Germany; they were patriots and Democrats. Marx was not. Wheen criticises Marxís querulousness, but always takes his side.

Rarely has a prophet done more to fulfill his own prophecy. As an angry old man, Marx disowned the German Marxists not because they were too extreme, but because they were too inclined to compromise with Bismarck. From his own ruthless conduct in the 1848 revolutions, it is evident that by the “dictatorship of the proletariat” Marx meant a one-party state. The libertarian Marx of the 1960s, whom Wheen wishes to rediscover, never existed.

Wheenís biography is not without merit: although it has no revelations, it incorporates much recent research. Above all, it is fluently and elegantly written. Here is Marx approaching the end: a wandering widower, banished to a warmer climate for his failing health, he writes to Engels: “I have done away with my prophetís beard and my crowning glory.” Wheenís commentary manages to be at once compassionate, shrewd and comical:

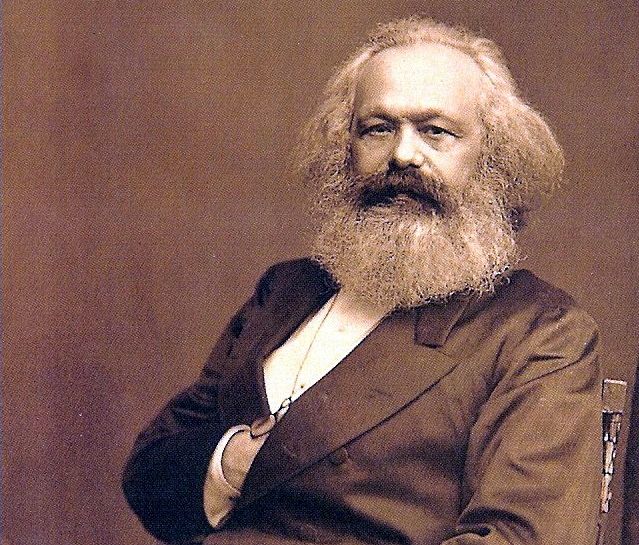

Eyeless in Gaza; hairless in Algiers. A bald, clean-shaven Karl Marx is almost impossible to imagine – and he made sure that posterity would never see him thus. Before the symbolic shearing he had himself photographed, hirsute and twinkle-eyed, to remind his daughters of the man they knew. It is the last picture we have: a genial Jupiter, an intellectual Father Christmas.

What a pity that Fourth Estate did not include this or any other illustration of Marx, his family or his colourful circle.

Mazzini described Marx as “a man of domineering disposition; jealous of the influence of others; governed by no earnest, philosophical, or religious belief; having, I fear, more elements of anger than of love in his nature”. No, Dr Marx was not a nice human being. Francis Wheen has done us a service by reminding us of the fact. As to whether Marx is still worth reading, this entertaining, often perceptive biography leaves us none the wiser.

Originally Appeared in the Telegraph