Originally posted by Peter Gray on his Psychology Today Blog.

Peter Gray is the author of Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life

In a study that preceded the one to be described here, my colleague Gina Riley and I surveyed parents in unschooling families — that is, in families where the children did not go to school and were not homeschooled in any curriculum-based way, but instead were allowed to take charge of their own education. The call for participants for that study was posted, in September, 2011, on my blog (here) and on various other websites, and a total of 232 families who met our criteria for participation responded and filled out the questionnaire. Most respondents were mothers, only 9 were fathers. In that study we asked questions about their reasons for unschooling, the pathways by which they came to unschooling, and the major benefits and challenges of unschooling in their experience.

I posted the results of that study as a series of three articles in this blog — here, here, and here — and Gina and I also published a paper on it in the Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning (here). Not surprisingly, the respondents in that survey were very enthusiastic and positive about their unschooling experiences. They described benefits having to do with their children’s psychological and physical wellbeing, improved social lives, and improved efficiency of learning and attitudes about learning. They also wrote about the increased family closeness and harmony, and the freedom from having to follow a school-imposed schedule, that benefited the whole family. The challenges they described had to do primarily with having to defend their unschooling practices to those who did not understand them or disapproved of them, and with overcoming some of their own culturally-ingrained, habitual ways of thinking about education.

The results of that survey led us to wonder how those who are unschooled, as opposed to their parents, feel about the unschooling experience. We also had questions about the ability of grown unschoolers to pursue higher education, if they chose to do so, and to find gainful and satisfying adult employment. Those questions led us to the survey of grown unschoolers that is described in this article and, in more detail, in three more articles to follow.

Survey Method for Our Study of Grown Unschoolers

On March 12, 2013, Gina and I posted on this blog (here) an announcement to recruit participants. That announcement was also picked up by others and reposted on various websites and circulated through online social media. To be sure that potential participants understood what we meant by “unschooling,” we defined it in the announcement as follows:

“Unschooling is not schooling. Unschooling parents do not send their children to school and they do not do at home the kinds of things that are done at school. More specifically, they do not establish a curriculum for their children, do not require their children to do particular assignments for the purpose of education, and do not test their children to measure progress. Instead, they allow their children freedom to pursue their own interests and to learn, in their own ways, what they need to know to follow those interests. They may, in various ways, provide an environmental context and environmental support for the child’s learning. In general, unschoolers see life and learning as one.”

The announcement went on to state that participants must (a) be at least 18 years of age; (b) have been unschooled (by the above definition) for at least two years during what would have been their high school years; and © not have attended 11th and 12th grade at a high school.

The announcement included Gina’s email address, with a request that potential participants contact her to receive a copy of the consent form and survey questionnaire. The survey included questions about the respondent’s gender; date of birth; history of schooling, home schooling, and unschooling (years in which they had done each); reasons for their unschooling (as they understood them); roles that their parents played in their education during their unschooling years; any formal higher education they had experienced subsequent to unschooling (including how they gained admission and how they adapted to it); their current employment; their social life growing up and now; the main advantages and disadvantages they experienced from their unschooling; and their judgment as to whether or not they would unschool their own children.

We received the completed questionnaires over a period of six months, and Gina and I, separately, read and reread them to generate a coding system, via qualitative analysis, for the purpose of categorizing the responses. After agreeing on a coding system, we then, separately, reread the responses to make our coding judgments, and then compared our separate sets of judgments and resolved discrepancies by discussion.

The Participants, and Their Division into Three Groups

A total of 75 people who met the criteria filled out and returned the survey. Of these, 65 were from the United States, 6 were from Canada, 3 were from the UK, and 1 was from Germany (where unschooling is illegal). The median age of the respondents was 24, with a range from age 18 to 49. Eight were in their teens, 48 were in their 20s, 17 were in their 30s, and 2 were in their 40s. Fifty-eight (77%) were women, 16 were men, and 1 self-identified as gender queer. The high proportion of women probably represents a general tendency for women to be more responsive to survey requests than are men. It is not the case that more girls than boys are unschooled; indeed, our previous study suggested that the balance is in the opposite direction — there were somewhat more boys than girls undergoing unschooling in the families that responded to that survey.

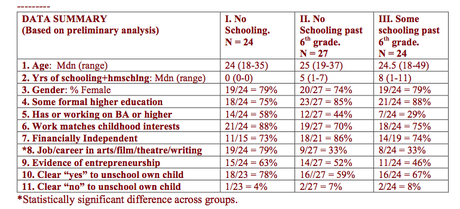

For purposes of comparison, we divided the respondents into three groups based on the last grade they had completed of schooling or homeschooling. Group I were entirely unschooled — no K-12 schooling at all and no homeschooling (the term “homeschooling” here and elsewhere in this report refers to schooling at home that is not unschooling). Group II had one or more years of schooling or homeschooling, but none beyond 6thgrade; and Group III had one or more years of schooling or homeschooling beyond 6thgrade. Thus, in theory (and in fact), those in Group II could have had anywhere from 1 to 7 years (K-6) of schooling/homeschooling and those in Group III could have had anywhere from 1 to 11 years (K-10) of schooling/homeschooling.

The table below shows the breakdown of some of our statistical findings across the three groups. The column headings show the number of participants in each group. The first three data rows show, respectively, the median and range of ages, the median and range of total years of schooling plus homeschooling, and the percentage of respondents that were female for each group. It is apparent that the three groups were quite similar in number of participants, median age, and percent female, but, of course, differed on the index of number of years of schooling plus homeschooling.

Their Formal Higher Education After Unschooling

Question 5 of the survey read, “Please describe briefly any formal higher education you have experienced, such as community college/college/graduate school. How did you get into college without having a high school diploma? How did you adjust from being unschooled to being enrolled in a more formal type of educational experience? Please list any degrees you have obtained or degrees you are currently working toward.”

I’ll describe their responses to this question much more fully in the next article in this series, where I’ll make ample use of the participants’ own words. Here I’ll simply summarize some of the statistical findings that came from our coding of the responses.

Overall, 62 (83%) of the participants reported that they had pursued some form of higher education. This included vocational training (such as culinary school) and community college courses as well as conventional bachelor’s degree programs and graduate programs beyond that. As can be seen in data row 4 of the table, this percentage was rather similar across the three groups.

Overall, 33 (44%) of the participants had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher or were currently fulltime students in a bachelor’s program. As shown in data row 5 of the table, the likelihood of pursuing a bachelor’s degree or higher was inversely related to the amount of previous schooling. Those in the always-unschooled group were the most likely to go on to a bachelor’s program, and those in the group that had some schooling past 6th grade were least likely to. This difference, though substantial, did not reach the conventional level of statistical significance (a chi square test revealed a p = .126).

Of the 33 who went on to a bachelor’s degree programs, 7 reported that they had previously received a general education diploma (GED) by taking the appropriate test, and 3 reported that they had gained a diploma through an online procedure. The others had gained admission to a bachelor’s program with no high-school diploma except, in a few cases, a self-made diploma that, we assume, had no official standing. Only 7 of the 33 reported taking the SAT or ACT tests as a route to college admission. By far the most common stepping-stone to a four-year college for these young people was community college. Twenty-one of the 33 took community college courses before applying to a four-year college and used their community college transcript as a basis for admission. Some began to take such courses at a relatively young age (age 13 in one case, age 16 in typical cases) and in that way gained a headstart on their college career. By transferring their credits, some reduced the number of semesters (and the tuition cost) required to complete a bachelor’s degree. Several also mentioned interviews and portfolios as means to gain college admission.

The colleges they attended were quite varied. They ranged from state universities (e.g. the University of South Carolina and UCLA) to an Ivy League university (Cornell) to a variety of small liberal-arts colleges (e.g. Mt. Holyoke, Bennington, and Earlham).

The participants reported remarkably little difficulty academically in college. Students who had never previously been in a classroom or read a textbook found themselves getting straight A’s and earning honors, both in community college courses and in bachelor’s programs. Apparently, the lack of an imposed curriculum had not deprived them of information or skills needed for college success. Most reported themselves to be at an academic advantage compared with their classmates, because they were not burned outby previous schooling, had learned as unschoolers to be self-directed and self-responsible, perceived it as their own choice to go to college, and were intent on making the most of what the college had to offer. A number of them reported disappointment with the college social scene. They had gone to college hoping to be immersed in an intellectually stimulating environmentand, instead, found their fellow students to be more interested in frat parties and drinking. I will describe all this more fully in the next article in this series.

Their Careers

Question 4 of the survey read, “Are you currently employed? If so, what do you do? Does your current employment match any interests/activities you had as an unschooled child/teen? If so, please explain.” Our analyses of responses to this question led us to generate a brief follow-up questionnaire, which we sent to all of the participants, in which we asked them to list and describe the paying jobs they had held, to indicate whether or not they earned enough to support themselves, and to describe any career aspirations they currently had in mind. Sixty-three (84%) of the original 75 participants responded to this follow-up questionnaire.

The great majority of respondents were gainfully employed at the time of the survey. Exceptions were some of the full-time students and some mothers with young children. Of those who responded to the follow-up questionnaire, 78% said they were financially self-sufficient, though a number of these added that their income was modest and they were financially independent in part because of their frugal lifestyle. Several of them described frugality as a value and said they would far rather do work they enjoyed and found meaningful than other work that would be more lucrative.

Collectively, the respondents had pursued a wide range of jobs and careers, but two generalizations jumped out at us in our qualitative analyses and coding of these.

The first generalization is that a remarkably high percentage of the respondents were pursuing careers that we categorized as in the creative arts — a category that included fine arts, crafts, music, photography, film, and writing. Overall, 36 (48%) of the participants were pursuing such careers. Remarkably, as shown in data row 8 of the table, 79% of those in the always-unschooled group were pursuing careers in this category. The observation that the always-unschooled participants were more likely to pursue careers in the creative arts than were the other participants was highly significant statistically (p < .001 by a chi square test).

The second generalization is that a high percentage of participants were entrepreneurs. Respondents were coded into this category if they had started their own business and were making a living at it or working toward making a living at it. This category overlapped considerably with the creative arts category, as many were in the business of selling their own creative products or services. Overall, by our coding, 40 (53%) of the respondents were entrepreneurs. As can be seen in data row 9 of the table, this percentage, too, was greatest for those in the always-unschooled group (63%), but in this case the differences across groups did not approach statistical significance.

In response to the question about the relationship of their adult employment to their childhood interests and activities, 58 (77%) of the participants described a clear relationship. In many cases the relationship was direct. Artists, musicians, theater people, and the like had quite seamlessly turned childhood avocations into adult careers; and several outside of the arts likewise described natural evolutions from avocations to careers. As shown in data row 6, the percentage exhibiting a close match between childhood interests and adult employment was highest for those in the always-unschooled group, though this difference did not approach statistical significance.

All of these generalizations regarding unschoolers’ subsequent employment will be illustrated, with quotations from the surveys, in the third article in this series.

Their Evaluations of Their Unschooling Experience

Question 7 of the survey read, “What, for you, were the main advantages of unschooling? Please answer both in terms of how you felt as a child growing up and how you feel now, looking back at your experiences. In your view, how did unschooling help you in your transition toward adulthood?”

Almost all of the respondents, in various ways, wrote about the freedom and independence that unschooling gave them and the time it gave them to discover and pursue their own interests. Seventy percent of them also said, in one way or another, that the experience enabled them to develop as highly self-motivated, self-directed individuals. Many also wrote about the learning opportunities that would not have been available if they had been in school, about their relatively seamless transition to adult life, and about the healthier (age-mixed) social life they experienced out of school contrasted with what they would have experienced in school.

Question 8 read, “What, for you, were the main disadvantages of unschooling? Again, please answer both in terms of how you felt as a child growing up and how you feel now. In your view, did unschooling hinder you at all in your transition toward adulthood?”

Twenty-eight of the 75 respondents reported no disadvantage at all. Of the remaining 47, the most common disadvantages cited were (1) dealing with others’ criticisms and judgments of unschooling (mentioned by at least 21 respondents); (2) some degree of social isolation (mentioned by 16 respondents), which came in part from there being relatively few other homeschoolers or unschoolers nearby; and (3) the social adjustment they had to make, in higher education, to the values and social styles of those who had been schooled all their lives (mentioned by 14 respondents).

For 72 of the 75 respondents, the advantages of unschooling clearly, in their own minds, outweighed the disadvantages. The opposite was true for only 3 of the participants, 2 of whom expressed emphatically negative views both of their own unschooling and of unschooling in general (to be detailed in the fourth article in this series).

Question 9 read, “If you choose to have a family/children, do you think you will choose to unschool them? Why or why not?” One respondent omitted this question. Of the remaining 74, 50 (67%) responded in a way that we coded as clearly “yes,” and among them 8 already had children of school age and were unschooling them. Of the remainder, 19 responded in a way that we coded as “maybe” (for them it depended on such factors as the personality and desires of the child, the agreement of the other parent, or the availability or lack of availability of a good alternative school nearby), and five responded in a way that we coded as clearly “no.” The five “no’s” included two of the three who were negative about their own unschooling experience and three others, who despite their positive feelings about their own unschooling would, for various reasons, not unschool their own child.

The fourth article in this series will delve much more deeply into the advantages and disadvantages of unschooling as perceived and described by these respondents.

Limitation of the Survey

A major limitation of this study, of course, is that the participants are a self-selected sample, not a random sample, of grown unschoolers. As already noted, relatively few men responded to the survey. A bigger problem is that the sample may disproportionately represent those who are most pleased with their unschooling experiences and their subsequent lives. Indeed, it seems quite likely that those who are more pleased about their lives would be more eager to share their experiences, and therefore more likely to respond to the survey, than those who are less pleased. Therefore, this study, by itself, cannot be a basis for strong claims about the experiences and feelings of the whole population of unschoolers. What the study does unambiguously show, however, is that it is possible to take the unschooling route and then go on to a highly satisfying adult life. For the group who responded to our survey, unschooling appears to have been far more advantageous than disadvantageous in their pursuits of higher education, desired careers, and other meaningful life experiences.

Stay tuned for the remaining three articles in this series (to be posted later, one at a time), where you will read much more about these grown unschoolers’ experiences, in their own words.

What are your thoughts and questions about this study, to the degree that I have described it so far, or about unschooling in general? What unschooling experiences — positive or negative — have you had that you are willing to share? This blog is a forum for discussion, and your stories, comments, and questions are valued and treated with respect by me and other readers.

About the Author

Peter Gray is the author of the book Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life.